REMINDER: don’t miss the upcoming INAUGURAL EPISODE of chiefmartecTV live with David Raab this Friday, June 10 at 2pm EDT.

Last week was a big week for marketing technology M&A news.

Two billion-dollar M&A deals: Marketo was acquired by private equity firm Vista Equity Partners for $1.79 billion and Demandware was acquired by Salesforce for $2.8 billion. (Granted, these deals aren’t closed yet, but for now, let’s take them at face value.)

What does this mean for marketers and the industry?

After reflecting on it for several days — I hate to make rushed, from-the-hip statements just for the sake of hitting a news cycle — I’m inclined to conclude: not a tremendous amount.

Sorry, you were expecting something more dramatic?

That’s not to say that either of these is a bad deal — for the acquirer, the acquired, or their respective customers. On the contrary, I think they’re both quite good for all parties involved. But neither one significantly alters the structure or dynamics of the industry.

Marketo’s deal isn’t industry consolidation — at least not yet

Let’s start with Marketo.

Marketo’s acquisition by Vista is not “consolidation.” It doesn’t result in fewer marketing technology vendors in the marketing technology landscape. Marketo remains Marketo, an independent company, albeit under new, private ownership.

Consolidation would have been if an existing marketing software giant — Adobe, Oracle, or Salesforce — had acquired them, particularly if they sought to phase out the Marketo platform as an independent offering and absorb it into a competing product. Someday the industry may see such large-scale consolidations, but we’re not there yet.

On the contrary, Vista’s acqusition significantly reduces the likelihood that Marketo will be absorbed in a pure consolidation play anytime soon. In the short-term, Marketo obtains:

- Deep-pocketed financial support for growth in sales, marketing, and R&D.

- A multi-billion dollar vote of “staying power” to assure customers of stability.

- A reduced risk of destructive consolidation at the hands of a competitor.

- Freedom from the often short-sighted quarterly demands of Wall Street.

- Potential benefits of a private vs. public company in stealth and agility.

These attributes are particularly valuable as Marketo executes its ambitious Project Orion, a bottom-up rearchitecturing of their platform around ultra-high-scale data engines. (The luxury of such a grand rewrite is not something that enterprise platforms easily carve out — but in a space such as ours, where so much has changed in the past decade since Marketo was first designed and engineered, it’s a powerful opportunity.)

Of course, Vista is in the business of making investments, and they’ll certainly want to exit with a nice return at some point. I’m going to estimate that’s at least two years out though — long enough to build up sufficient return.

It’s possible that they may sell to a direct competitor — true consolidation — at that time. But if Marketo is successful, it will likely be more valuable to buyers who would want to nurture that growth even further, either (1) a larger enterprise not fully in this space yet (e.g., Microsoft is a great example, which is why they were rumored to be a likely suitor in this most recent round), or (2) the public markets again, who may greater appreciate Marketo at a different scale under different circumstances.

So this is not consolidation today, and may not be even a couple of years from now.

That being said, there are possible consolidations that could result from this deal:

- Vista could provide Marketo with capital to make more acqusitions.

- Marketo’s continued growth in marketing automation (and related categories) could further reduce opportunities for small players in that space, driving the industry towards more of an oligopoly.

- Vista could combine Marketo with other marketing tech ventures in its portfolio — for instance, Cvent — to attempt to create a larger enterprise marketing software company with a bigger footprint (although it would be highly unusual for a PE firm to orchestrate something like that).

I think the first two are likely. The third not so much, but an interesting thought exercise.

However, as an ironic counternarrative to consolidation, it’s possible that the Vista deal may also promote greater diversity in the marketing tech landscape, intentionally or unintentionally:

- Strengthening Marketo’s ISV ecosystem (intentionally). Marketo has championed a platform strategy more vocally than many of their peers with their LaunchPoint program. I think it’s an underappreciated strategic asset, but one that still has incredible potential. As Marketo grows, the dynamics of such a platform should naturally feed a virtuous cycle: a larger customer base attracts more ISVs, which in turn attracts more customers, and so on. But if Marketo and Vista put more weight behind this — for instance, a richer set of APIs for Project Orion combined with a greater marketing effort on an open marketing platform position — they could accelerate those dynamics significantly.

- Enabling key Marketo employees to start new ventures (unintentionally). Marketo alumni have already started two marketing technology companies — Captora and Engagio. With the all-cash deal from Vista, a number of other employee stockholders may decide it’s time to set off on their own. And what domain do they have the most expertise in? Applying software to marketing. Surely they’ve observed many other challenges that marketers still face that they may seek to tackle entrepreneurially. After all, the Vista deal reminds everyone that successful founders can reap huge financial rewards.

Salesforce acquiring Demandware is a challenge to IBM, Oracle, SAP

The acqusition of Demandware by Salesforce is slightly closer to industry consolidation — where there were two logos on the marketing tech landscape before, albeit in completely different categories, there will now only be one.

But that strikes me as mostly corporate, not product, consolidation: Salesforce did not compete with Demandware, nor vice versa. On the immediate horizon, it’s unlikely to significantly change the dynamics of who buys Demandware as an e-commerce platform and what they do with it. Perhaps it marginally helps the Demandware platform’s perception of longevity in the market — but they were already perceived as a strong, indpendent public company.

The main effect of this deal is to position Salesforce — the company — as a growing competitor to IBM, Oracle, and SAP. Each of those competitors have had a strong e-commerce offering (IBM Commerce, Oracle ATG, SAP Hybris). With the growth of digital commerce as an increasing priority for businesses, this was an increasingly significant gap in Salesforce’s portfolio. (The same is true for Adobe, which I heard was interested in Demandware as well, so Salesforce may have been extra happy to snatch it up.)

Again, I think this is generally good for Salesforce, Demandware, and their customers.

But I’m skeptical of how deeply Salesforce will integrate Demandware with the rest of their products. Sure, there will be some cross-product enhancements that will be helpful. But it’s not clear that those cross-product wirings will be significantly better than what is achievable through their respective APIs and ISV support capabilities — certainly Salesforce has been an ISV superstar with its AppExchange and Demandware has a very impressive ISV community in its LINK Marketplace.

Salesforce will certainly get leverage from having Demandware in its portfolio — particularly with its enteprise relationships and growing partnerships with major systems integrators and marketing service providers.

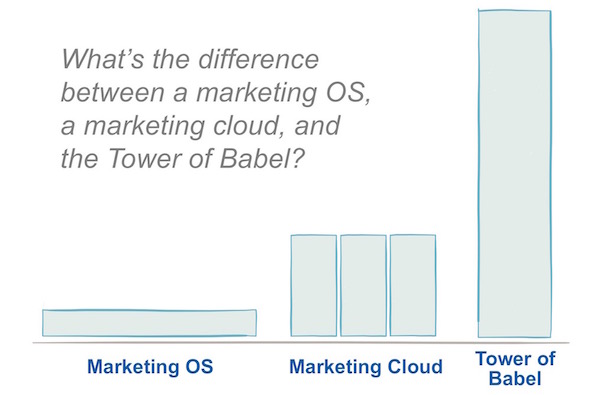

But there’s a reason that, for instance, Oracle’s ATG e-commerce platform is not tightly integrated with their Eloqua (B2B marketing), Responsys (B2C marketing), or BlueKai (DMP) products. These are each massive products in scale and scope on their own. Maintaining and innovating each of them independently is a Herculean undertaking. Attempting to combine each of these incredibly complex products into some fully entwined “superstack” strikes me as the marketing software equivalent of the Tower of Babel.

There are architectural advantages to keeping the major components of a “marketing cloud” relatively independent of each other. In software development terms, Salesforce’s acquisition of Demandware is more like “horizontal scaling” than “vertical scaling.” But I think that’s what makes this a good, solid move.

What do you think?