I just came from an excellent meeting with local colleagues who lead some of the best known non profits in town. We were talking about a number of things, but one topic was the emergence of social impact bonds (SIBs) as another method of financing social/health programs. Social Impact Bonds are very new and the first one occurred in Great Britain in 2010. Today, there are 14 social impact bond projects in the United Kingdom, one in Australia, and a couple or so in the United States (as of 2013). There are none yet in Canada.

To say that there is wide spectrum of opinion about these bonds would be an understatement. There are sector leaders dead set against them, others who are cynical but still engaged in the dialogue, and still others who are what I would call “soft” advocates. Fewer still are actually putting time and resources into the development of initiatives that could be financed by a social impact bond.

My organization, Bissell Centre, is one of the few, and I guess you could also call me a “soft” advocate for SIBs. More about that later, but for now, in case you aren’t sure, here is some information about SIBs, taken from the website of Finance for Good, which is the company we have contracted with to help us with our SIB exploration.

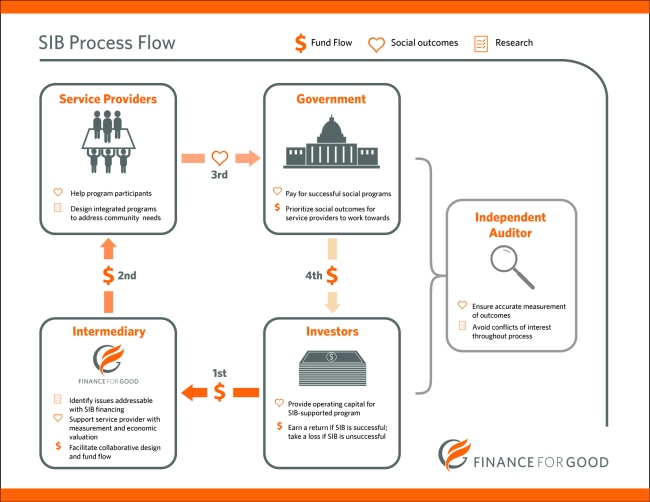

“A social impact bond (SIB) is a pay-for-success contract where a commissioning body – typically the government – commits to pay for the achievement of a particular desired social outcome.” There are four “players” in a SIB: the government, the service provider(s), private investors, and an intermediary organizations (like Finance for Good) that connects all the players together. Take a look at the diagram below:

I will let you investigate on your own how SIBs work and you can do so at the Finance for Good website but there are also other sources you can take a look at as follows:

There is also this video from McKinsey and Company (produced from an U.S. context):

Because SIBs are new and largely an unproven alternative method of financing large scale social impact initiatives, there is a lot of uncertainty about them as well as debate about whether or not we should actually try them. I lean on the side of trying them out, but don’t for a minute think that is a simple stance. Trying SIBs on for size carries significant risk and I suggest the first SIBs in Canada that actually are implemented will experience problems, unexpected side turns, and continued criticism from those who are against them.

So, before I talk about why my organization is moving forward with a formal SIB exploration with the Alberta Government, let me spend a little time sharing some of the key questions and issues about SIBs.

1. Advocates for SIBs all seem to start with a principle that I am not sure I agree with and that is that governments do not have sufficient funds to resource social innovation, large scale change, and more effective impact models and systems. This rote acceptance that there just isn’t enough money to ignore the potential of SIBs requires discussion and I mean real discussion.

Point in fact that the entity that has the most money (and power) to effect and support transformational change in how social programs are designed and delivered is the government or should I say, the three levels of government. I think it is facile to just buy into the position that the government can’t afford large scale impact projects. It may be prudent for all of us to recognize that the government does choose what it will and will not support with public funds. These choices means somethings get money – often plenty of it – and others get less or nothing. This reflects an old Taoist saying: “for every yes there is a no.”

I don’t know how many times I have heard government funding bodies (at all levels), not to mention other non-government funders tell me (and my colleagues) that they have no money for this or that. In reality, these funders have a lot of money; the key question for me is, again, about how and where they choose to invest those dollars.

Funding reform must include such an investigation and, if the investigation is serious and authentic, I propose that one result would be a reallocation of significant amounts of money away from some things toward others that are more promising in terms of achieving desired and priority impacts. This is true as well for funds that are allocated to areas outside of the social sector; perhaps there are dollars spent to support other sectors that should be redirected to social impact projects. Of course, I am not suggesting that there are unlimited dollars, but I am saying it is too easy to let governments (and other major funders) off the hook by accepting a foundational premise that there is no longer any substantive funds to invest in social programs.

As well, governments are political and often funding decisions are made that placate constituencies or that position the ruling party in a favorable position for the upcoming election. What is funded may also be impactful, but often it is the political-ness of funding that is at the core of what influences decision-making.

By the way, successful SIB projects will result in the government funding them, which necessarily means they have the money, albeit at a later date.

2. There seems to be agreement among the majority of those pitching social impact bonds that it is a good thing that governments mitigate their risks in terms of resourcing innovations and large scale impact projects by transferring the risk to private investors. I am not sure why that is a good thing. One could argue that governments who wish to avoid the risk involved in finding new and better services for their people will end up losing capacity to be innovative themselves and I am not sure I want our governments to lack that ability. As well, transference of risk likely carries with it a transference of accountability. We should be careful about supporting such a transfer by government to the private sector.

3. One of my colleagues at today’s meeting is concerned about the monetization of the sector’s work and reducing social good ventures to being solely measured by financial measures. “Pay for success bonds” which is often what SIBs are called, doesn’t sit well with him, and I get it.

I am not supportive of any financing method that sees helping people as only having value if it can have financial benefits to the government or any funder for that matter. I believe SIBs can be structured that aren’t simply limited to financial measures, but more to the point I see SIBs as one method of financing for those social programs that can be measured in large part through financial measures.

4. There is concern that investors will pull out of a SIB project if for whatever reason they don’t like what is going on. The risk is that the initiative will be significantly hurt or worse close down because of such a withdrawal of funds. This concerns me, too, and from where I sit would have to be adequately satisfied with the SIB contract before I would sign it. In the financial sector there are investments that are locked in. Perhaps SIBs need to be structured that way.

5. Many are concerned that SIBs threatens philanthropy among major givers or foundations. In other words, fundraising groups like United Way and to be honest, my own organization, could discover, for example, that a major donor is taking her $200,000 donation away from the organization to invest it in a SIB. I wouldn’t like that either; however, we must all recognize that systems change can both benefit and harm individual organizations. I suggest that the impact on organizations is one reason why systems change is so difficult. We want it, but not if if the change hurts our own operations.

6. Another concern is based in ideology. One voice at the meeting against SIBs thinks it is wrong that an investor makes a profit off of successful social programs. For example, an investor puts in $1 million and the successful SIB returns to her $1.1 million, a profit of 10%. This will seem wrong to some. On the other hand, if the same investor gave a donation of $1 million she would receive a larger sum back in terms of a tax reduction. We all seem to be ok with that. How come? What’s the difference?

One difference is that a donation of $200,000 is truly given away; the donor does not get it back. In the example above, if the donor is going to donate the same amount the following year, she has to come up with an additional $200,000. In the SIB context, she would invest $200,000 and get that principle back plus interest. She could then turn around and in a sense recycle the same $200,000 in another SIB. One could argue that such an investor, if truly philanthropic, might participate in both major giving and SIB financing, thus increasing participation in doing social good.

7. Some critics point out that the administrative costs of a SIB will be significantly higher than mainstream funding mechanisms. Complex contracting will cost more money than standard contracts to negotiate and finalize. More use of legal counsel will add to the cost as well. Then there is the expense of designing and delivering on the evaluation, which I surmise will be more complicated the most evaluations. My guess the government will have to spend more time and money on its own oversight of SIBs than it does on traditional contracts, at least during the formative years. The intermediary organization also gets a cut by the way, though I am not sure of how much.

The question is will such costs still make the investment viable in terms of a return and will such costs render it impossible or improbable that the service provider can deliver on the outcomes with so much of the investment being spent on administrative actions? This is actually one of my major concerns.

8. The last issue about SIBs I will cover here (I have no doubt there are more than the eight I have mentioned) is this: to what extent is it really possible to apply financial metrics to the outcomes of a program? So many variables will enter in like changes to the economy that could influence results either way; changes in life circumstances that can remove a client from the program and thus render the investment in him or her unfulfilled. For example, if a single mother is doing well in a SIB financed employment program but five months in gets married and pregnant, those normative life experiences could remove her from the program. How will that be dealt with in the measurement of success and of course how will such life circumstances impact the final decision about achievement and the return on investment?

So, you might thinking to yourself, “I thought you were in favour of SIBs.” It’s true that I see issues with SIBs. It is also true we are, nevertheless, working on an initiative that we currently envision being supported by a SIB, but if I decide to go forward with it (assuming the government is willing and investors come into the mix), I need to be thinking about the aforementioned issues and objections and be confident that they are or can be adequately addressed before I sign a contract. It’s simply good stewardship to do so. This is why I call myself a “soft” advocate for SIBs.

What I am really doing (not really advocating to others) is stopping myself from saying “yes” or “no” to a SIB arrangement earlier on in my thinking and deliberations. There are many stages of a SIB development and I can pull out at any of the stages if needs be. I certainly won’t sign a deal that I do not feel is appropriate. The governance system in my organization does not require me to seek approval to seek SIB financing from my board; however, our governance system does not stop me from seeking approval. Given the newness and complexity of SIBs, not to mention the wide variety of opinion about them, I certainly envision doing that.

So what are the reasons why I am leading a SIB development in my organization?

1. Notwithstanding the fact that I don’t buy into the rationale that governments have no money for large scale investments on their own or that governments should transfer risk to non-government investors, I see SIBs as one more way to potentially finance the sector’s work. SIBs are not relevant for all social programs and not all non-profits will be able to deliver on a SIB, but I suggest SIBs are niche form of financing large projects that is worth a serious look. And a serious look, for me, includes investing some money and time into the efforts of exploring whether or not SIB financing is feasible for our initiative.

2. Somewhat related to point #1, I do not know of any funder locally, including government funders, that will entertain a proposal, for example, to fund an initiative over five years at a total costs of $5 million. Most funders I am dealing with have frozen their funding for many years now and none of our current funders (and we have many), have the capacity to entertain such a large scale proposal.Well, the government does have this capacity but it has no system in place to do so. That reality makes SIBs attractive and are another reason why we are investigating whether or not we should participate in one.

3. SIBs offer a new and deeper way to collaborate with the government. Even the process we are a part of currently is different, involving having a series of “conversations” about our project, the measures, the structure of funding, how we will work together to evaluate, and so forth. In fact, if the government just asked us from the get-go to submit a proposal up front, I would see that as a sign that the government is not fully understanding all that must take place beforehand to even get to the proposal stage. We need to do this together, and I am hoping it is possible that we can be a part of a “true” partnership about doing impactful work for Albertans. Being an early adopter in the SIB world allows us to not only engage governments in new or different ways, it allows us to influence the principles and processes that governments will identify as they become more operational of SIBs.

4. While some fear that the work of the service agency will end up in the controlling hands of investors, I do not have that fear because of how the SIB is or should be structured. As well, I will not sign a contract that places control of our mission work in the hands of an investor or investor group. Actually, I believe that if we can find the right investors — those interested in innovation, for example, and perhaps even entrepreneurial approaches to doing good — we might have a better chance of being successful because the nature of a SIB is such that the government is not controlling every aspect of our service offering, much less subjecting us the annual cycle of bureaucracy that is the norm with conventional funding programs.

One colleague of mind asked me if I would feel like I have wasted time and money if we don’t go ahead. My answer is no. The initiative we are designing is one I want my agency to do regardless. Without SIB funding it will be more difficult to launch. We might have to start smaller or take longer to ramp up, but much of our time and investment so far has been in the design of a program we believe in and will be committed to bring to fruition. Our investment is no different or larger than dollars and time we invest in the design of other programs we seek funding for.

Another perspective on this is that non-profits also need to take some risks to test new waters. Smaller organizations or those suffering from financial woes may not be able to do so, but our organization is larger than most, typically adequately funded, and we can afford the very small financial investment we have made in the process. As well, I approach all innovative undertakings as a type of change lab that helps us learn about what we do, how we do it, how collaboration works and doesn’t work, and how to form new or different relationships. In other words, I believe the capacity of my organization to continue to be innovative and effective requires us to move to the edges of the status quo, albeit with discipline and an acute awareness of risk.

While I would never admonish those who have no desire to explore SIBs or advocate that they should do so, my view is that we need transformational change across our sector and our exploration of SIBs is one of our contributions to that exploration. That means this is a choice we are making; it doesn’t mean those who make a different choice are wrong.

I will try to write more about our SIB journey in future postings.