I wonder.

Have we have been hoodwinked. co-opted, and led to the altar of a false god – or at the very least, an imperfect one?

Back in the early days of outcome proliferation, we were told – some say promised –outcomes would save the day. They would be good for us, direct us to our potential, help us understand the demonstrable differences we were making in our important work.

Funders and agencies would dance together to harmonious music like true partners. Priorities would crystalize and we would at last experience full taste of that old maxim: proof in the pudding.

I recall discussions happening everywhere and I remember one meeting doodling on my yellow pad, sketching out a muscle bound hulk in a cape with Outcome Man angled across the crest. A friend mused out loud later over wine that the acronym, OM, gave outcomes a spiritual mien, perhaps even something a tad cultish.

Before too long, consultants hired by funders were out spreading the word. Goals and objectives sat shunned in the corner or had to go outside to the back lanes of our common ground and hunker together like smokers.

Meanwhile new language filled our boardrooms: outcome measurement, indicators, and perhaps the most life-changing words of all: logic model, the new ritual.

I recall being interviewed in the early days by one of the hired advocates about what I thought of the rapid move to outcomes. My response was short: Don’t do it. I was pressed to elaborate. It’s going to be a huge mess, I said.

Unfortunately, the momentum was too strong, like a wildfire in the wind. Outcomes were the promised land.

The other day I was talking with a few colleagues about what I sense to be the mythology of transformation we have been embracing in our sector. I wondered out loud about the lack of transformative conversations across the non-profit sector that are actually producing transformation. Not all agreed with me – the usual fare – though, for some, their disagreement was attached to fear, fear of upsetting funders who, I inferred, would bring out their vengeful knives and cut organizations that opposed the status quo.

Punitive actions by some funders have occurred of course, but I imagine such perniciousness is no more common than funded agencies spinning fictions of success from nebulous data.

Sarcasm aside, my experience – and I believe the experience of most of us – tells me that funders, agencies, and community leaders are serious about their transformational intentions.

What slows all of us is, among other things, the dread of the unknown and the prospect of losing the comfort we derive from the status quo.

Outcomes measurement and its various derivatives (Social Return on Investment, results-based funding, etc.) is not without merit, but the problem is that we have ordained it to be the answer and subsequently we don’t even think collectively about how outcomes are not helping us, if not working against us.

Our faith in outcomes is resolute even when we harbor secret thoughts about its fallacies. It’s very similar to how we have positioned collaboration in our sector as a must-do, so much so that agencies seek ways to force its presence in order to satisfy rote calls for its predominance in funding proposals.

I am not naïve. I know outcomes are too systemic now to be replaced and to be honest I am not sure it should be, but how we see outcomes and how we use them really isn’t working as much as we had once envisioned.I suggest, as well, that if we are honest, it is not working as well as we tell one another it is.

There are at least four major issues I have with our outcome-focused system.

Outcomes can confine our thinking.

A focus on outcomes can work to corral our thinking and strategic engagement of one another into a set of diagrams and steps. As well, the methodology of creating an outcome model stresses the importance of best practice, evidence-based practice, and assessing one’s actions against benchmarks set by others. In the outcomes world, we seek the comfort of proof and somehow don’t observe ourselves in dialogue with others about the impossibility of proof in the work we do.

This corralling effect perpetuates what I believe is a systemic bias against the outlier, the boat rocker, and those who offer wild ideas for consideration. Outcomes are too often about the neat and tidy and, not the messy thinking that often is what conjures up big innovations or even radical change.

Yes of course there are exceptions. There are innovations taking place in various pockets of our various sectors. Some funders have demonstrated capacity and interest in initiatives that truly test the status quo. But these noble efforts are not enough for there to be a sector wide transformative movement.

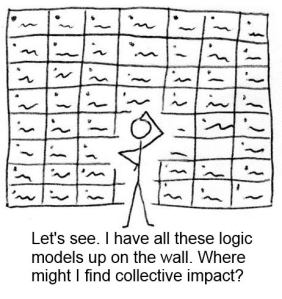

There is no evidence of collective impact.

Our systemic dedication to outcomes measurement has not yet produced substantive evidence of how all this logic model work has made a difference across the community, much less if the model actually is an improvement over the golden days of goals and objectives. I have not seen a comprehensive analysis on just how much outcomes measurement costs. It has to be well into the millions locally.

What I do know is that the advance of outcomes measurement and the significant costs it has added to the budgets of non-profits have not been accompanied by appropriate resources to support the work.

There are examples of funders collaborating to standardize the outcomes they want from agencies and to create common language and aligned expectations. Progress seems very slow on this front, however. The big question for me is, other than saving time to fill out forms, will such collaborations further our desire to be able to demonstrate collective impact?

My reaction to such collaboration is mixed. Part of me affirms such the intent. In our current context, it makes sense for funders to do this, and doing so may be part of the journey toward a common impact statement about all the myriad outcomes we expect from agencies.

Another part of me wonders if the pursuit of common outcome statements risks simplifying the complexity of community life into an evaluation schema that is too general and perhaps the result of too many compromises.

There is no objective proof.

The dependence on hard proof of results is unnerving. Also, we know that much of what we accept as proven is actually subjective renderings of the proof. There is little objectivity anywhere. Very little objective truth.

The proof we desire may not even be the proof we should be delivering. How, for example, is it ascertained that the outcomes we choose to pursue are the “right” outcomes?

The thesis is that by focusing on outcomes, organizations will make adjustments to meet them, when required. It makes sense. But are the adjustments the right ones? One reason why outcomes are ineffective is that they try to simplify complexity and, as well, they can lead to changes in actions that are taken to meet the outcome measure even if doing so may not really improve results.

Example. If one major outcome of a school system is to achieve 100% high school graduation (of course we can all debate if this is an outcome or a goal or something else), such an outcome by itself does not speak to the quality of the education, how relevant it is to the current environment, and so forth. As well, we all intuit that such an outcome is not achievable but we want to get as close to it as we can.

Now perhaps this is the cynical side of me, but I suggest that one way to increase the graduation rate is to institute a policy to not issue failing grades. This is what has happened in the Edmonton Public School system. Clearly, making failure impossible is one way to increase graduation rates, but the higher rate achieved likely will not increase the learning of students, much less ready them for the real world, where failure is measured and has consequences.

Meeting outcomes does not significantly change what is funded.

Another issue for me is that the achievement of outcomes does not seem to significantly motivate change in terms of what funders choose to support, how much they allocate to what, or for how long. Sure there are multi-year funding agreements but in the majority of cases, such long-term funding has not been implemented to further the achievement of outcomes as much as they have become a way to keep funding frozen over extended periods of time.

In a recent conversation with a funder, I was pleased to hear the many affirmations of my organization’s work and how effective my staff is in meeting desired outcomes. Within a minute, I was also being told that the upcoming three-year agreement would see no increases. I realize there is a limit to the global pot of funding; however, it seems reasonable to expect that major funders will also be reallocating existing funds to where successes are taking place.This may be happening to some extent, but I am not sure there is sufficient transformational funding going on. At least not yet.

HOW MANY EVALUATION REPORTS DO WE NEED TO UNDERSTAND WHAT WE ARE ACCOMPLISHING?

Unfortunately all too often, funding decisions are based on politics and systems-wide decisions that do not allow for variances in how funding is applied. Everybody gets frozen, for example, which one can easily argue is not how an outcomes based system should work.

In my experience, with one exception, I cannot recall sitting down with one funder to go through an analytical discussion about whether or not outcomes were achieved.

Actually I spend more time talking about budgets, activity reports, financial condition, and at times about why I have to give money back to funders because of a surplus. The latter is especially rankling because if the program met outcomes, we have delivered on the contract. Isn’t this what results based funding is about?

On the flip side if your program meets outcomes but runs a deficit, no help is offered as a general rule. Of course this isn’t just about outcomes; it is about how, when push comes to shove, outcomes are secondary to money and big and small “p” politics, at least for many funders.

I don’t imagine my views are popular in some settings. And I am sure there is ample disagreement with what I am putting out there. I welcome the disagreement. My whole point is we, as a sector, are avoiding these types of discussions, especially about those elements of our practice we just perpetuate without substantive reflection.

Please share your comments and any other ideas you have about what should be front and centre in our transformational conversations.

I can be reached here: [email protected]