Let’s face it: marketing is in a big data bubble.

That’s both a “big data” bubble and, more generally, a big “data” bubble. Everyone is talking about data, big data, data analytics, big data analytics. Vendors, analysts, consultants, pundits, bloggers, etc., are all falling all over themselves to squeeze these terms into their propaganda content marketing.

As just one example, three out of the Top 10 predictions for CMOs by IDC revolve around data. How CMOs must have a strategy for how market-driven data will contribute to corporate objectives (#1). How CMOs will be in jeopardy if they fail to produce a robust data analytics function (#4). How 50% of all new marketing hires will now have a technical background as the CMO scrambles for data analytics proficiency in the department (#5).

In fact, the subtitle of IDC’s accompanying webinar was Today’s CMO Becomes a Master of Data.

Now, I love data as much as the next techy-geeky-marketing-wonk-with-a-blog. But what strikes me about all this explosive data chatter — in no small part, driven by the peaking hype cycle of big data as a miracle drug — is how little recognition is being given to the operational implications of actually using data.

For instance, IDC’s predictions for 2013 state that the CMO will be given full responsibility for “data analytics” — and, in some unspecified way, required to tie that to business growth. The hiring of people with technical backgrounds in marketing is expressly for “data analytics proficiency.” The wholesale replacement of legacy CRM infrastructure is justified by “greater insight into the revenue impact of marketing and sales.”

That’s an awful lot of data, analytics, and insight — but not much committed action beyond observation and fodder for internal meetings with PowerPoint. It’s as if the plan is roughly:

- Analyze data — preferably big data.

- ???

- Profit.

This feels eerily analogous to the dot-com bubble of the late 90’s to me (substitute “analyze data” with “capture eyeballs”) in two ways.

The bubbly part of the big data bubble

First, the expectations of what big data will deliver on its own, especially in the short-term, are massively overblown. Lots of people are throwing lots of money at the promise that big data will, somehow — I don’t know how exactly, it’s technical and mathy — tame the fractured, fragmented, frenzied landscape that is modern marketing and crunch all of those complications into more customers. All as a well-oiled machine.

Regrettably, it’s not that simple.

A smaller set of articles — alas, reasonable pragmatism doesn’t generate nearly as many page views as wide-eyed prognostications of marketing data rapture — have explained why. Michael Wu, an analytics scientist, wrote a great piece on The Big Data Fallacy on TechCrunch, explaining why data is not the same as information, which is not the same as insight — a good place to start.

Gord Hotchkiss tackled the question of whether big data will replace strategic thinking (short answer: no), writing, “There seems to be one assumption that I believe is fundamentally flawed, or at least, overly optimistic: that human behaviors can be adequately contained in a predictable, rational, controlled closed-loop system.” He draws upon Justin Fox’s book, The Myth of the Rational Market, which illustrates the dangers of oversimplifications inherent in modeling — and how that disastrously played out in the financial crisis of 2008.

Actually, it turns out that this debate about the limits of data goes back 200 years. Media researcher Yaakov Kimelfeld recently wrote a Metrics Insider column titled A Demon Under the Streetlight that explains how this overreaching data-has-all-the-answers delirium is a reincarnation of Laplace’s demon. The 19th-century mathematician Laplace postulated that if you knew everything about the exact state of the universe at any one moment in time, you could then perfectly extrapolate everything about the past and the future. As Kimelfeld point out in his article, however, “Big data is not all of the data.” Not even close.

Even The New York Times felt the need to point out the inflated expectations of data in marketing in a Sunday feature, Can Social Media Sell Soap? (Short answer: maybe, but not necessarily the way people first thought.) Stephen Baker calls “the belief that with enough data, all of advertising could be turned into quantifiable science” a trap. “Even as researchers swim in data that previous generations would have swooned over,” he writes, “They struggle to answer crucial questions regarding cause and effect. What action can I take to get the response I want?”

You get the point. Big data is not a panacea. Beware of tulip mania.

The real revolution: from big data to big testing, big experience

However, there’s a second way in which this big data bubble resembles the dot-com bubble: underneath the hype, a truly major revolution is happening.

For all the silly dot-coms that skyrocketed to great fame — and then self-imploded when reality intruded on their business models — the Internet did go on to fundamentally transform business on a massive scale. Amazon, Facebook, and Google — all pure Internet companies — are widely considered three of the four horsemen of the global tech world today. But their businesses are about more than capturing eyeballs. Eyeballs are there, but it’s a small piece of a bigger picture.

The real data revolution in marketing won’t be a sugar-coated miracle pill that anyone can adopt simply by buying some software, hiring a data scientist, and pointing them at a cloud full of data. The real revolution in data will be a change in organizational behavior and culture — and those changes are hard and take time. Many organizations will struggle with the shift, and frankly, many will be usurped by new competitors who grow up natively with this new worldview.

So what exactly is the real revolution?

It’s not data. It’s not even data analytics. It’s being data-driven.

I know, that sounds pointlessly subtle, but bear with me. As Mark Twain would say, this is the difference between the lightening and the lightening bug. Being data-driven is not the same as just embracing data and analytics. Data and analytics are small pieces of a bigger picture.

The bigger picture: creating an organization that can confidently experiment, innovate, and adapt on a broad scale. Being truly data-driven embeds this deeply into an organization’s culture.

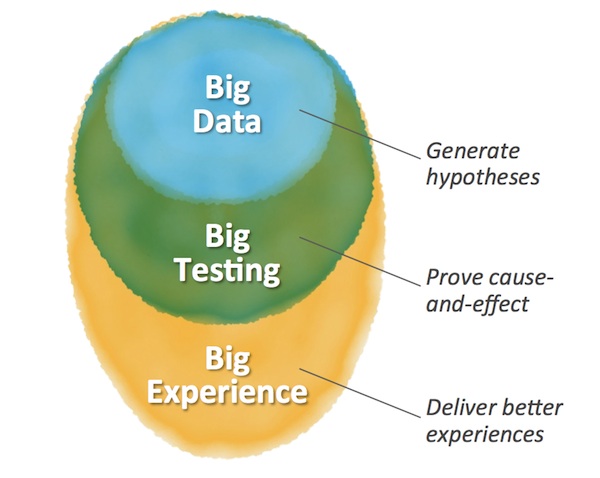

There are three parts to this, which I’ve illustrated at the top of this post:

- Collect and organize data and wield tools to extract information and insight from it. This is the part that big data has to offer. But some of the most valuable output from such data analytics will be mere hypotheses — interesting correlations of factors and behaviors in ever-more-finely-sliced customer segments that may have meaningful impact. But these are only seeds of ideas, possibilities

- Take those hypotheses and be able to quickly and effectively test them to prove cause-and-effect: that those factors can indeed be leveraged to influence customer behavior. Empowering many people throughout your organization to run these tests — and to fearlessly test big ideas — is a large-scale transformation to organizational behavior and culture that we can call big testing.

- Apply your targeted data and proven tests towards delivering better customer experiences — through the web, mobile devices, call centers, in-store and in-person interactions, etc. It’s not just making the same experience better for everyone. It’s delivering more specialized experiences to many different customer segments. This mission is big experience.

There’s plenty written about big data out there, so we won’t elaborate further on that part — other than to reemphasize that it is predominantly about analysis, not action. It’s by connecting big data to big testing and big experience that you turn that analysis into action. That’s modern marketing alchemy: transforming lead (data) into gold (better, more profitable customer experiences).

But it’s worth expanding a bit on what’s meant by “big testing” and “big experience” — and why they’re such a big leap for most marketers.

Making a big deal out of big testing

A few months ago, I wrote a post, “We want to test bold, new ideas that always work.” It highlighted recent research by the Corporate Executive Board showing that the far majority of Fortune 1000 marketers think their organizations are not effective at test-and-learn experiments. One reason why: at least half didn’t think an experiment should ever fail.

I believe this is the single biggest obstacle most organizations face: their culture and politics dissuade people from trying experiments because failure of an experiment implies failure of the tester. Who wants to stick their neck out in that environment? So either people don’t test anything, or they test in a non-controlled manner so that outcomes are comfortably subject to caveats and interpretations.

Or — and I’ve seen this in landing page optimization for years — they limit themselves to extremely minor, in-the-weeds tests, such as tweaking the words in a headline or changing the button color on a shopping cart. Such superficial tests risk little, but they rarely gain much. Perhaps the greatest damage they do is that they give people the illusion of engaging in real experimentation. (“Sure, we run tests all the time!”) The Shakespearean label for that kind of testing: full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Big testing is qualitatively different.

There are three ways in which big testing earns its “big” label:

First, it’s about testing big ideas. Headlines and button colors are fine, but they barely scratch the surface. The real power of testing is unleashed when you use it to learn ways of engaging entirely new segments of customers or to pioneer innovative new ways of selling or delivering your product or service. It’s about taking the surprising insights that big data may reveal and proving (or disproving) their value and efficacy.

There’s a classic post by Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup, that explains why learning is better than optimization. “The right split-tests to run are ones that put big ideas to the test. For example, we could split-test what color to make the ‘Register Now’ button. But how much do we learn from that? Let’s say that customers prefer one color over another? Then what?”

A good way to know if a test is truly meaningful or not: state out loud what the hypothesis is. If there is no hypothesis, or it’s something patently banal — like “chartreuse green buttons will have at least a 0.01% increase in clicks over forest green buttons” — then you’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Second, big testing is not restricted to a tiny priesthood of test-masters who jealously guard the data, tools, or governance rights for running tests. Big testing empowers and encourages an open, big team of testers across the organization. Many different people are given the capability to run tests in the context of their particular work.

Big testing is analogous to social media marketing in this regard. The best social media programs today thrive when they have contributions from a wide array of participants throughout the organization. Of course, this is usually best when there’s a strong shared vision and some basic training — enough to keep people loosely coordinated and out of trouble. But harnessing a (relatively) large and distributed force is a source of great power — both in sheer manpower and in rich diversity of ideas.

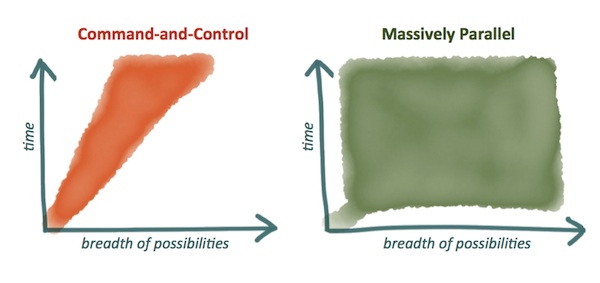

I think of this as massively parallel marketing — a nod to massively parallel computing that makes the processing of big data feasible. Massively parallel marketing makes the taming of the fractured, fragmented, frenzied landscape that is modern marketing possible.

Massively parallel marketing covers a much broader set of possibilities much faster, but it is a fundamentally different kind of organization than the traditional command-and-control hierarchy.

Third, and perhaps most important of all, big testing is a big deal in the organization. It’s championed by executives from the top-down. Experimentation isn’t a risk to your job. On the contrary, not experimenting — in particular, not experimenting with big ideas — will put you out of favor.

I was at a big data conference a month ago where Gary Loveman, CEO of the Caesars casino empire, gave a presentation about how important meaningful testing is in his organization. “There are three ways to get fired from Caesars,” he states matter-of-factly. “You can steal from the company. You can harass a co-worker. Or you can fail to have a control group for an experiment.“

That’s making a big deal of testing.

At that same conference, Hal Varian, the chief economist at Google shared that Google runs around 10,000 experiments per year, with about 500 experiments going on at any one time. Testing is an integral part of their company culture.

It’s worth pointing out that both of these companies are superstars when it comes to big data, but in both cases, they strongly emphasized the criticality of running real-world tests to capture the value buried in that data. As Hal Varian said simply, “Experimentation is the gold standard of causality.” It tells you which actions generate the best response.

Big experience makes a big impression on the customer

“It’s completely meaningless when the fulcrum point between big data and big experience is a 120×120 pixel banner ad vying to interrupt your game of Paper Toss,” wrote Adam Kleinberg in an insightful AdAge article titled Don’t Let Growth Fool You: Mobile Advertising Is Still Failing. Amen, brother.

The incredible potential of big data — and big testing, for that matter — is near worthless if an organization can’t employ it in the service of delivering remarkable customer experiences. Big experience should be the big tent under which big data and big testing sing and dance.

There are three important connections between big experience and big data/big testing:

First, data and testing give direction to the burgeoning customer experience movement. Customer experience is becoming the banner under which modern marketing marches to victory. It’s why everything is now marketing. The tectonic shift of marketing’s responsibilities, from mostly customer communications to increasingly lifecycle customer experiences, is one of the 5 meta-trends of modern marketing.

It’s an opportunity for marketing to shine at the highest level of the organization.

But as marketing seeks to qualitatively improve customer experience — to differentiate themselves from the competition in big ways in the minds of their audience — they face a dilemma. Building amazing customer experiences is a lot of work, time-consuming, and expensive. Taking a “build it and they will come” messianic approach may have worked for Steve Jobs, but that’s hard to replicate predictably.

Using big data and big testing provide a structured and systematic way to hone in on the right experiences to build big. Designers and customer experience professionals can leverage these capabilities to identify rich, new pockets of opportunity for exploration, as well as to refine their productions along the way. Done properly — where big data and big testing are employed in the service of remarkable customer experiences — the relationship between these parts can be harmonious, not contentious.

Data and testing minimize the downside and maximize the upside of pursuing big, new customer experience innovations.

Second, big testing is often only valid if the customer experiences in which it’s executed are good. If you run a split-test of two concepts, say offer A (a price emphasis) and offer B (a quality emphasis), testing a hypothesis of which will motivate a particular customer segment more — but both experiences are kind of crappy — then the results of your test are useless.

Probably both will perform poorly, but maybe offer A gets slightly more traction. But it’s not unequivocally because the market prefers price over quality. The audience exposed to offer B may have found the offer of high quality, juxtaposed with an experience that stunk of low quality, to be incongruous and have no credibility. Superficially claiming “quality” is not the same as truly exuding quality.

At the very least, the customer experience can’t detract from the test. But it’s far better if big testing is a comparison of two very good customer experiences to see which is best.

Third, possibly the most profound, is that big data and big testing give us a way to construct amazing customer experiences around customers rather than products.

See, even though we know we’re largely past the age of mass marketing — at least in terms of channels and touchpoints — the mindset and organizational structure of most businesses still revolves around fixed products and services. Even as they try to embrace a more customer-centric way of selling those products and services, they’re still anchored to segmenting their market by product at their core.

“Most companies count their profits in terms of products, not customers,” remarked Gary Loveman at that conference in answer to the question of why most companies are so bad at using analytics to drive better results.

The real vision of big experience is using data and testing to reconfigure our organizations around our different groups of customers, finding and favoring the most profitable and crafting ever more tailored experiences to each. I’m not saying that lightly — I appreciate how big of a challenge that is. But ultimately, that is how businesses will unlock the massive value that the big data movement is promising.

Data is fuel — invest more in the engine

So let’s circle back to where we started.

In the face of all this data mania in marketing, the real revolution is shaping a data-driven organization. Wrangling big data is an important part of that, but big testing and big experience are the ways in which that data lead is turned into customer gold. While there is certainly cool technology available to power that entire “big stack,” the biggest part of embracing this revolution will be shifting your organizational structure, behavior, and culture to truly leverage it.

Let me wrap up with this analogy:

Data is like fuel. It’s certainly valuable, and there’s a big industry emerging around the extraction, refinement, and distribution of that fuel. Hey, Exxon Mobil is a $400 billion mega-corporation.

But the big oil companies would be nearly worthless without the transportation industry. Because it’s the engines and the cars and the jet airplanes that use that fuel to move the world. An engine without fuel is fairly useless; but a barrel of fuel without an engine is equally pointless.

It’s only the two together — the fuel and the engine — that unleash the potential of both.

If you want to really harness the power of big data, build the organizational engine to use it. That’s the bigger future that marketing is headed towards. And it will be as big of a worldwide revolution as the rise of the Internet.