Darling, I don’t know why I go to extremes

Too high or too low there ain’t no in-betweens

— Billy Joel

There’s a common fallacy known as a false dilemma or false dichotomy. It’s where you’re artificially presented with a black-and-white, either-or choice: you’re forced to choose between all of one or all of the other. “Your either with us or against us!”

It’s a fallacy because, most of the time, you’re not actually constrained to just those two choices. There are many great options in the middle — and often even more outside of that narrowly framed continuum.

In modern marketing, however, I’ve been noticing that more and more issues are being framed as black-and-white, either-or choices. We seem more ready than ever to take a new idea and either reject it completely or embrace it to the point of absurdity. The “reasonable middle” seems to get relatively little voice, even though in most cases, a balanced approach is optimal.

Consider these examples, topics that generate much debate at the extremes but in actuality benefit from a healthy dose of moderation:

Inbound marketing. Inbound marketing (and permission marketing before it) is the native son of the Internet: using good content marketing, organic SEO, social media marketing, and subsequent email-driven nurturing to win customers by fulfilling their quest for knowledge is an incredibly powerful paradigm. Outbound marketing, such as advertising, direct mail, sponsorships, event exhibits, sales calls, and other mainstays of traditional marketing, is on the other end of the spectrum. But while these are very different approaches, however, there’s no reason why a company shouldn’t do both — each to the degree that they provide ROI and have a positive brand impact. There are even a plethora of hybrid tactics, such as pay-per-click (PPC) advertising in search and social media.

Data-driven marketing. Relying solely on gut-based, experience-driven decision-making in marketing is foolish in the digital age. It’s so easy to leverage analytics and experimentation to make better decisions. But going overboard, believing that data has all the answers — what Kate Crawford has labeled data fundamentalism — may be even worse than ignoring data entirely. Data fundamentalism allows you to make incredibly stupid decisions with a high degree of statistical confidence. Again, the sensible answer for most companies is a balance of data analytics and human judgement.

Marketing technology governance. Should marketing leave all technology strategy and management to the IT department? In the digital world, probably not. But does that mean that marketing has to become 100% compartmentalized in all technology it uses? Of course not. There are many reasonable compromises and collaborations between those two poles, where marketing teams develop native technical leadership capabilities while also partnering and coordinating with IT. A chief marketing technologist can be the bridge between marketing and IT, not a crocodile in the moat.

Agile marketing. Traditional management approaches are often top-down, strict command-and-control hierarchies. But in our digitally malleable and rapidly shifting world, such corporate structures struggle to adapt to ever more fluid markets. Agile management approaches, which give a lot of power to bottom-up creativity and talent, are much better suited to this environment. But for most companies, the optimal approach will be a combination of the two. The best agile organizations naturally blend consistent top-down vision and values with bottom-up imagination and insight.

In all these scenarios, it’s not a strict either/or proposition.

You can do great inbound marketing and great outbound marketing. You can embrace data-driven decision making and apply human reasoning and the insights of experience. You can collaborate with IT and have your own marketing technology responsibilities. You can have strong top-down leadership and adopt agile marketing for the parts of your marketing mission that benefit from it.

So why don’t these more balanced approaches get more attention?

Hype cycles, maturity models, and other self-inflicted wounds

I believe there are 7 reasons why the extremes in modern marketing get more air time than they deserve — and by calling them out, I hope it will make it easier to keep them in check:

- Gartner’s hype cycle.

- A mental bias for either-or decisions.

- Maturity models.

- Up-and-to-the-right graphs.

- Conflating advocacy with absolutism.

- False trade-offs — e.g., art/science is not really a trade off.

- Content marketing escalation.

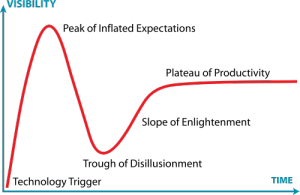

The first is Gartner’s hype cycle. Marketing actually created the hype cycle, perfecting the art of sensationalizing new technologies to generate buzz, news clippings, and higher valuations. But the peak of inflated expectations — overpromising and underdelivering — inevitably leads to the trough of disillusionment. Many companies (and careers within them) are damaged by this precipitous fall.

The irony is that marketing is now a victim of its own hype cycle dynamics. These days, it’s the marketer who is the target of the hype. The hype for new social media platforms, the hype for big data, the hype for new marketing technologies, etc. And the rate of new cycles being thrown at marketers is now so rapid that, even as they each run their course, most CMOs are being pulled up at least two or three peaks of inflated expectations at any point in time.

But here’s the thing: a hype cycle can only seduce you if you let it. You don’t have to flat out ignore a new technology either. You can take a modest position of skeptical curiosity and a willingness to test the practical uses of something new.

In Chip and Dan Heath’s new book, Decisive, they call attention to a number of psychological quirks in our decision-making instincts. One of them is our tendency to get trapped in narrow frames — such as either-or decisions. This is the false dilemma fallacy.

However, by recognizing this bias, we can consciously broaden the frame of our decision, considering “and” instead of “or” — or exploring entirely different options.

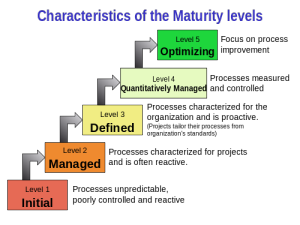

Another culprit of overreaching expectations is the maturity model. No doubt, you’ve seen these: four or five stages that organizations progress through — or supposedly should progress through — in developing a certain capability along a number of dimensions. One of the original maturity models was for software development, CMM (Capability Maturity Model). Since then, there have been an explosion of maturity models, from big data to social media. Even I’m guilty of producing one, a search marketing maturity model five years ago. (Has the statute of limitations expired?)

The problem is that each stage typically promotes advancement on all dimensions of the model — pushing every aspect of the company’s “maturity” further and further into the stratosphere. The implicit assumption is that you should always want to move up to the next stage.

But that may not be the right thing to do. There is a cost to everything, and advancing into the highest levels of a maturity model may have diminishing returns or even negative returns for you. For instance, with that original maturity model for software, CMM, it has been observed that many of the world’s leading software companies — Apple, Microsoft, Symantec — never advanced beyond the first or second stage.

Real maturity is discovering which stage is optimal for your business, or even mixing attributes from different stages — resisting the narrow-framing of a fixed set of homogenized stages (that were likely assembled by someone with their own marketing agenda).

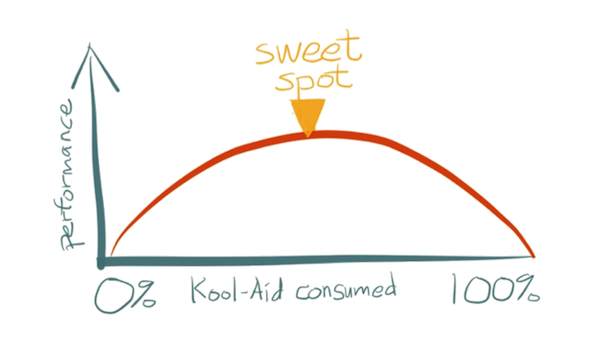

A more generic version of maturity model madness is the up-and-to-the-right graph. So many promotional materials emphasize up-and-to-the-right graphs: do more of X, get more of Y. And who doesn’t want more? More clicks, more leads, more customers, more revenue, more profit, more, more, more.

Which is great — but again, everything has a cost, even if it’s just opportunity cost. The pursuit of “more” without considering what those costs are leads to absurdity. If one blog post a week gets us 10 prospects, and one blog post a day gets us 20 prospects, then we should publish a blog post every second to take over the world! Just because the line on the graph can go higher and further to the right doesn’t necessarily mean you should chase it there — at the expense of other variables that aren’t represented on that graph.

The antidote: common sense and more holistic cost/benefit thinking.

Conflating advocacy with absolutism happens when we’re excited and passionate about something that is clearly good, but we slide from merely embracing it to embracing it at the exclusion of other things. Other things that didn’t need to be excluded. For instance, data-driven decision making is a wonderful thing. Use data as much as you can. But that doesn’t have to be at the exclusion of leveraging experience, intuition, and human judgement — especially in deciding what data to use and in recognizing what’s reasonable to extrapolate from it.

Related to that is the notion of a false trade-off, taking two things and erroneously claiming that there is an inverse relationship between them — that more of one inherently means less of the other. The example I’m thinking of is the debate between art and science in marketing. It’s implied that more science means less art. But that’s certainly not true in the real world: more physics does not mean less poetry.

Of course, in the context marketing, “art” is often meant as more qualitative and intuitive factors, in contrast to “science” as more quantitative and analytical factors. Storytelling through written, spoken, and visual expressions is also considered “art” in marketing (although it’s really more of a craft). Whereas analytics, data mining, and controlled experiments such as A/B testing are considered more “science.”

But still, even with those fuzzy definitions, modern marketing can — and should — synthesize methods from both the “art” and the “science” categories. They’re not necessarily trade-offs. Great science in marketing can direct the application of great art in marketing, and vice versa — for instance, there’s an art to running great marketing experiments, if you can wrap your head around that juxtaposition. And let’s not forget that science itself is a creative endeavor.

Last but not least, content marketing escalation. There’s a heated content marketing arms race underway. Marketers are being pushed to generate more and more content, faster and faster. But there are two deleterious “hype cycle” side effects of this.

First, topics that seem to be trending are rapidly added to content marketing agendas. Quick, we need a white paper on something with big data! This causes an acceleration of content on a topic that can make it seem even hotter, which attracts the attention of more content marketers, and so on, like feedback from a microphone next to an amplifier. In the interest of speed-to-publish, not all of these content pieces are, um, deep or original. Let’s just say that there are a lot of echoes in the shallow end of the pool. But those echoes don’t offer independent corroborating evidence of that trend.

Second, because there is suddenly a flood of content on that new subject, everyone is vying for attention in a crowded field. This can create pressure to produce something that has “shock value” — something surprising or controversial. Such things are often found on the edges of a continuum rather than in the middle, which can artificially skew the perception of the edges being greater than the middle.

Moderate and nuanced articles and reports don’t necessarily make for “sexy” content marketing. But I personally believe that more pragmatic content can be more useful to real prospects. In an environment where we marketers are the consumers of content marketing, not just producers, we can influence this dynamic. We can seek out the real over the sensational and use social signals (or the absence of them) to give our fellow marketers clear feedback on what we really want.

(To be fair, certainly a number of marketers do set a high bar for their content marketing. But as a group, they’re probably at least one standard deviation above the mean. Maybe two.)

Pragmatic marketing is marketing in a Technicolor world

The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.

— F. Scott Fitzgerald

I’ve said it many times: it’s an exciting but challenging time in marketing. We’re in a period of enormous disruptive innovation, an intellectual and creative melting pot of old and new strategies, tactics, capabilities, and worldviews.

The last thing a marketer should do these days is resist change.

In fact, I believe that most marketers should lean into an “early adopter” mindset. Be willing to learn about and experiment with new ideas as they emerge. This is important not because those new ideas will bear fruit immediately — some will, some won’t, and probably none of them to the degree that their initial streak up the hype cycle might proclaim — but because engaging on the vanguard of such changes helps marketing be more attune to broader shifts in markets and society.

Marketing should be the “early warning” signal for changes that will effect the business. Since adapting to change is probably the most challenging thing for any organization to do, having a head start on a new trend, gaining some early experience and familiarity with it, lays the groundwork to more rapidly embrace that trend at scale — if and when that’s warranted.

Not every trend will blossom. Many will fizzle out. But placing little bets on a number of emerging opportunities lets you hedge against both possible outcomes. Even those that don’t take off can provide some valuable insight into how the world is evolving. Marketers must stay hungry to understand their customers — and that’s always a moving target.

And by continually scouting the frontier and experimenting with new ideas, marketing increases its overall metabolism for change. That is a precious capability in a world of constant and accelerating change. It’s part of why I believe marketing, more than any other group, has the potential to break free from the innovator’s dilemma.

So am I advocating two contradictory principles here?

- Don’t fall prey to the inflated hyperbole of new ideas.

- Embrace new ideas with the mindset of an early adopter.

Is this a paradox?

I don’t believe it has to be. We can take the pragmatic approach of balancing both in some reasonable proportion to each other. Granted, that denies us the simplicity of black-or-white positions and deflates the false dilemmas that give rise to so many sexy blog post titles.

But it leaves us with the far more interesting challenge of painting marketing in a vibrant Technicolor world.