We know the power that one person can have on our lives. We each have heroes, villains and role models who permeate into our lives and indirectly guide the way we behave. Steve Jobs introduced the world to the love of design. Sheryl Sandberg inspired many to “Lean In” (and many others to “recline”). Nikola Tesla inspired many people to go into science.

So it shouldn’t be surprising that one individual can also permanently change the destiny of a company. More importantly, these individuals often aren’t even a part of the organization – they’re clients, they’re friends, or they may even just be acquaintances.

In case you’re ever doubting your worth as a professional, or as the supporter of a company, or second-guessing why you put so much time and energy into your relationships, remember how just one small contribution could change the trajectory of an entire company. (After all, most people begin their buying process with a referral.) It’s happened many, many times in the past, and we’ve chosen to highlight five specific examples from companies you know about.

Here’s how five individuals and their decision to advocate for a company changed entire company trajectories and their roles in history:

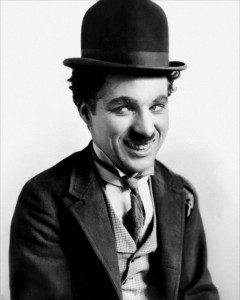

1. Charlie Chaplin for The Walt Disney Company

This may make you raise your eyebrows: filmmaker Charlie Chaplin played a key part in the development of The Walt Disney Company. According to Neal Gabler’s biography entitled Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, the character of Mickey Mouse was even based on a combination of Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks. (Can you see it?)

This may make you raise your eyebrows: filmmaker Charlie Chaplin played a key part in the development of The Walt Disney Company. According to Neal Gabler’s biography entitled Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, the character of Mickey Mouse was even based on a combination of Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks. (Can you see it?)

Chaplin’s direct involvement with Disney began when the company left Columbia Studios to sign a deal to distribute their short films with United Artists, where Charlie Chaplin was a co-founder. A couple of years later, Walt Disney began exploring the possibility of creating a fully-animated feature film, but according to Gabler, United Artists “didn’t seem eager to provide a substantial advance.”

Eventually, Walt signed with a larger studio, RKO, to expose Disney’s first feature film, Snow White, to a wider audience. As Gabler wrote, “In the end, with the blessings of the united artists themselves – Chaplin wrote [Disney’s chief legal counsel] Lessing that ‘I don’t want to make any money on Walt, and anything I can ever do for him I will gladly perform’ – the Disneys departed.” It was far more than the typical empty promise that comes with amicable departure.

Shortly after, the Disneys needed an independent producer to guide them with negotiations for RKO. Chaplin offered to share his records and experiences – and his ledgers from his film Modern Times – to enable the Disneys to negotiate the same terms that Chaplin had gotten in international markets. After Snow White premiered, Walt would thank Chaplin for his “invaluable service” and write, “Your records have been our Bible – without them, we would have been as sheep in a den of wolves.”

Shortly after, the Disneys needed an independent producer to guide them with negotiations for RKO. Chaplin offered to share his records and experiences – and his ledgers from his film Modern Times – to enable the Disneys to negotiate the same terms that Chaplin had gotten in international markets. After Snow White premiered, Walt would thank Chaplin for his “invaluable service” and write, “Your records have been our Bible – without them, we would have been as sheep in a den of wolves.”

Snow White would go on not only to significantly contribute to Disney’s reputation – it became the highest-grossing American film to that point in history, and their cut of the revenue would allow Disney to make their next two feature films, Pinocchio and Fantasia.

2. Robert Scoble for social messaging app Yo

In early May of 2014, product evangelist and tech blogger Robert Scoble paid a visit to social mobile photo and video-sharing network Mobli’s offices in Tel Aviv. Mobli CEO Moshe Hogeg had something new to show him – an app called Yo. According to Business Insider, Scoble told Hogeg, “This is the stupidest, most addictive app I’ve ever seen in my life.” Nonetheless, perhaps out of amusement, Scoble decided to upload a post of Yo on Facebook and share it with his 600,000 followers. That set off the chain reaction for which Scoble has become so well-known.

In early May of 2014, product evangelist and tech blogger Robert Scoble paid a visit to social mobile photo and video-sharing network Mobli’s offices in Tel Aviv. Mobli CEO Moshe Hogeg had something new to show him – an app called Yo. According to Business Insider, Scoble told Hogeg, “This is the stupidest, most addictive app I’ve ever seen in my life.” Nonetheless, perhaps out of amusement, Scoble decided to upload a post of Yo on Facebook and share it with his 600,000 followers. That set off the chain reaction for which Scoble has become so well-known.

Scoble’s post made it to the eyes of Dan Leveille, who exposed it to Product Hunt, a product discovery community. Financial Times reporter Tim Bradshaw, who saw Yo through Scoble’s Facebook post and on Leveille’s Product Hunt entry, contacted Yo’s Or Arbel and wrote a post about about the app.

That was the beginning of Yo’s exposure to mainstream media. According to VentureBeat, Yo gained over two million users after launch. Scoble’s simple share on Facebook was exactly what Yo needed to get started on their press push and build a solid starting user base.

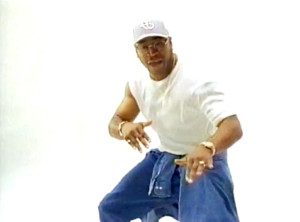

3. LL Cool J for clothing company FUBU

A single commercial launched a modest side project (for an entrepreneur who started with ten T-shirts) into a multi-million dollar clothing company – and the entrepreneur didn’t even have to pay for it! In the late 90s, rapper LL Cool J helped a little-known streetwear company called FUBU increase sales exponentially in just a matter of months.

FUBU as founder Daymond John worked at Red Lobster, selling his apparel out the back of a van. Eventually, he and a few of his co-founders pitched in for $40,000 for a trade show in Las Vegas, and returned with $400,000 worth of merchandise. John’s wife also happened to go to high school with LL Cool J. (Here’s some advice in case your significant other didn’t attend high school with influencers in your field.)

The opportunity provided itself when The Gap hired LL Cool J to shoot a commercial. As Steve Stoute writes in The Tanning of America: “This was how the opportunity to be just such an ambassador arose for LL when he was hired by the Gap in 1997 to help them reclaim some of the luster of coolness that they were beginning to lose. And what LL Cool J did to seize the moment remains, to this day, one of the most unapologetic, bold, and daring things I’ve ever seen anyone do in my life.

“Upon arriving at the set to shoot his commercial, LL happened to be wearing a FUBU hat, and as he came out of the dressing room in his Gap outfit, he decided not to take it off. A wardrobe coordinator might have told him to remove it, but when he didn’t, nobody persisted.”

“Upon arriving at the set to shoot his commercial, LL happened to be wearing a FUBU hat, and as he came out of the dressing room in his Gap outfit, he decided not to take it off. A wardrobe coordinator might have told him to remove it, but when he didn’t, nobody persisted.”

The result was this Gap commercial, in which LL Cool J wears a FUBU cap and mentions the company by name in the lyric, “For Us By Us – on the low.” As FUBU founder Daymond John recalled on Jimmy Kimmel, The Gap put $30 million into airing that advertisement, which ultimately skyrocketed FUBU’s sales. The commercial originally aired in spring of 1997. By 1998, according to Fast Company, FUBU’s sales were $350 million.

4. Oprah Winfrey and beauty products line Carol’s Daughter

Whenever Oprah endorsed a product on The Oprah Winfrey Show, the product would be exposed to mainstream attention and gain massive amounts of users. The change is so dramatic that it has been dubbed “The Oprah Effect.” This is what happened with natural hair product company Carol’s Daughter in 2002.

As written in Entrepreneur magazine, “Before the appearance the natural hair care line was generating $2 million in yearly revenue and seeing on average 200 website clicks a day. When Carol’s Daughter made its debut on Oprah, the site crashed after having 17,000 visitors in 10 seconds. Fortunately, it recovered and next year’s revenue skyrocketed to $20 million.”

5. Roy Brenholts for The Wall Street Journal

As unbelievable as it sounds, automotive companies were even sneakier a half-century ago than they are today. In 1954, The Wall Street Journal published an article which revealed that GM and other automotive companies were trying to limit advertising of cars from smaller, independent dealers so that the public would not learn of lower prices. This was a risky maneuver for the Journal because GM, Ford, and Chrysler were the nation’s three largest newspaper advertisers and the Journal relied particularly heavily on automotive advertising.

GM subsequently canceled all their advertising in the Journal and cut the publication off from weekly auto production figures. The Journal, receiving letters of support and criticism from their community, published a few of them in their newspaper. One reader, Roy Brenholts, wrote the following: “I have two Cadillacs and a Ford. I was considering trading the Ford for a Chevy. Now I will trade for another Ford. I had considered one Cadillac for a new one. Until General Motors tells you they will stop their Hitlerite attitude I will not consider another Cadillac.”

Kilgore wrote back to Brenholts, “I appreciate your support of our editorial position I just don’t think that differences of opinion in one particular field should be allowed to spread into others,” but forwarded a copy of this letter and his own reply to GM chief Harlow Curtice. Curtice, recognizing his mistake, lifted the press ban on the Journal and resumed advertising in the paper.

As highlighted in Restless Genius, “[Author] Edward Scharff later concluded that this ‘new-won reputation was worth inestimably more than the General Motors advertising account.’ Donald MacDonald, then a junior ad salesman but later head of all sales for the Journal and Dow Jones, summed up the implications simply: ‘Our future was assured.’”

Brenholts’ advocacy enabled the Journal to maintain its relationship with GM, while allowing for its editorial integrity to shine. “The battle with General Motors would, forever after at the Journal, be remembered as a watershed…The Journal had gained immeasurably in prestige and was continuing to gain in readers.”

Closing thoughts

With each of these companies, it would have been necessary for someone — though perhaps not necessarily these specific individuals — to advocate for these companies in order for them to blossom. Such is the power of advocate marketing, an emerging discipline that helps companies ignite business growth by leveraging the voices of customers, partners and other fans.

Not every advocate has to have the influence of some of those featured above; more often than not, they’re just regular people who are trusted by their peers. Watch Influitive’s ongoing video series for weekly conversations between advocates who are making a huge impact on the brands they love and the marketers who run advocate marketing programs for those companies.