This is a high level article for the top sales leader in the company. Your title may be CSO, CRO, SVP of Sales, or Sales VP. It doesn’t matter. If you are the one individual at the top, you’ve asked yourself this question:

“If this doesn’t get fixed, will I get fired?”

Everyone who ever held the top job has asked themselves this at some point. You are working 14 hour days to make the number. Still, it’s natural that at times you wonder what the personal cost might be. We hear a lot of stories. Some from clients, but many more from our personal networks. Lately it seems like there’s been a rash of top sales leader terminations. I reached out to some of my SBI colleagues and they concurred.

Last year, Matt Sharrers and Greg Alexander wrote a 32 page e-book. It’s called Promoted to VP of Sales: The Year One Toolkit. Download it here. Take your tenure out of the equation: read this to survive and succeed.

This e-book was originally written for new Sales VPs. I’m convinced that all sales leaders should read it. Why do I say this? I reviewed 8 specific recent termination situations for this article. I determined that every single one stemmed from one of 4 root causes. All 4 root causes are covered in this book. The 4 root causes are:

- Thrashing. The wrong solutions implemented due to incorrectly diagnosed sales problems. Result: lots of effort but few positive outcomes.

- Detachment. Sales strategy chosen with incomplete understanding of industry/company/product. Result: go-to-market plan is not in sync with target markets.

- Sequencing. Poorly ordered programs that cancel each other out. Result: see #1 above. Change fatigue sets in.

- Alienation. No appreciation for day-to-day impact on rest of the company/your peers. Result: misalignment with peers in other roles. Sales leaders cannot be successful in a vacuum.

For the rest of this article we’ll focus on 2 of the items above. We’ll look at Sequencing and Alienation. These were the 2 root causes I saw most often in my research. We’ll examine the stories of Marshall and Kirk. They are composite characters built from common elements of the termination reviews I conducted. For a deeper dive on all 4 root causes, download the e-book here.

Sequencing

Marshall had been CSO of a software company for 2 years. He made enormous changes, but in the wrong order. For example, he didn’t move fast enough on the global account program. 40% of revenue came from 19 accounts. Marshall didn’t realize where the growth had to come from. He didn’t resource these accounts appropriately fast enough. Then, at the end of Year One, he decided to dramatically revise compensation plans. However, much of his revenue came from channel partners. There was a deep rift between his Channel VP and his VP of Direct. The comp changes were positive, but these 2 subordinates were in a cage fight. Their boss was the loser. Marshall should have revised the rules of engagement first.

In Year Two, Marshall attacked other sales improvement initiatives. He found the money to buy a new CRM. But his sales process was broken. Marshall knew this and planned to fix it soon. In the meantime, the CRM was optimized with the broken sales process steps. Rep adoption was 27%. They just didn’t see the benefit of the new CRM. It was a pain to use.

Marshall’s CEO was on year 3 of his tenure. He was missing the number. The board was pressuring him. He needed a scapegoat. Marshall had made himself an obvious choice. He failed to sequence his initiatives. Had he used a thoughtful approach to planning, he might have survived.

Alienation

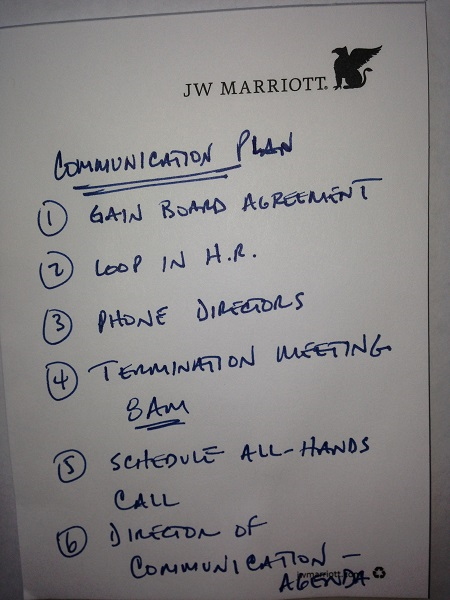

Kirk’s story is simple. He didn’t build enough early political consensus and trust. He worked in a legacy business services company. The company was growing slightly faster than the GDP. The CEO initially empowered Kirk to make sweeping changes. The mandate was “get us growing faster than the rest of our industry.” Kirk came out of the gate strong, but his ready, fire, aim approach hurt him. He needed BU leader support to roll out changes. Many egos were involved, since he operated in a matrixed organization.

At first, Kirk’s colleagues were cautiously neutral. But Kirk didn’t win them over. He used his mandate as a club, instead of fostering collaboration. Over time, his colleagues became passively, and eventually actively, resistant. They began to privately “update” the CEO. Nothing unprofessional, and not much open complaining. But the CEO lost faith in Kirk’s ability to work within the org structure. Kirk blamed “politics.” However, the fault was his.

Don’t let inertia or ego cause you to fall into one of these traps. Learn from the work of Matt Sharrers and Greg Alexander. The information in this e-book, thoughtfully applied, can help you avoid many pitfalls. Wouldn’t it be great to enjoy the journey instead of worry?