In November of last year, I spoke at the CX NXT – Customer Experience Summit in Dubai on the topic of failure, fumbles and fiascos in customer experience.

Now, we can all learn from failures, but rather than just doing a talk about service and experience mishaps and what we can learn from them specifically, I wanted to try and elevate the discussion to illustrate that failure is inherent in every organisational system and is something that we need to both acknowledge and do something about.

To do that, I told three stories about different experience failures that had rising degrees of severity and impact on both the customers and the organisations involved.

The first story featured something that I had written about before: a locked door to a temporary toilet for people with disabilities. The lesson being that the way that we design and manage experiences is often not inclusive. In this particular story, the assumptions that were made about what could happen if that toilet was left unlocked directly impacted the very people for whom that facility was provided.

The second story featured the experience of a man who had $10,800 (£8,500) stolen from his HSBC bank account as part of a scam, and then he and his family spent 20 hours on the phone trying to contact the bank to report this and have his account restored. The insight here was that the messy middle of customer service exists, something I have also written about before, and this can have a huge impact on customers who suffer from problems that can’t be answered by a knowledge base article, solved through the use of self-service tools or via an interaction with a customer service agent. Incidents like this can often happen when the issue requires somebody in the middle office, back office, or another team to do something to help solve a customer’s problem or resolve an issue.

The final story featured a bloodied and dishevelled Dr. Dao, who was forcibly removed from his seat on a United Airlines evening flight from Chicago to Louisville in 2017 after he refused to give up his seat, saying that he had to get home as he had patients to see in the morning. If you know the story, it was a triumph of process over common sense. But, the situation was made worse when the CEO of United Airlines at the time, Oscar Munoz, wrote a letter defending his staff and accused Dao of being “disruptive” and “belligerent.” This whole incident caused a huge PR storm and knocked billions of dollars off United’s share price. Munoz subsequently issued an apology, taking full responsibility for the issue and promised to work to make things right. It didn’t end there. Dao sued for damages, and United settled for a confidential amount. Some sources estimate that the settlement was somewhere in the region of $140 million dollars.

These experiences were not caused by bad actors but were caused by unintended consequences that came about as a result of poor assumptions, a lack of due care and attention to an infrequent occurence and a catastrophic over adherence to process and rules rather than common sense.

But, what they also illustrate is that the potential for bad experiences is built into the organizational systems that we design and inhabit.

Consider this.

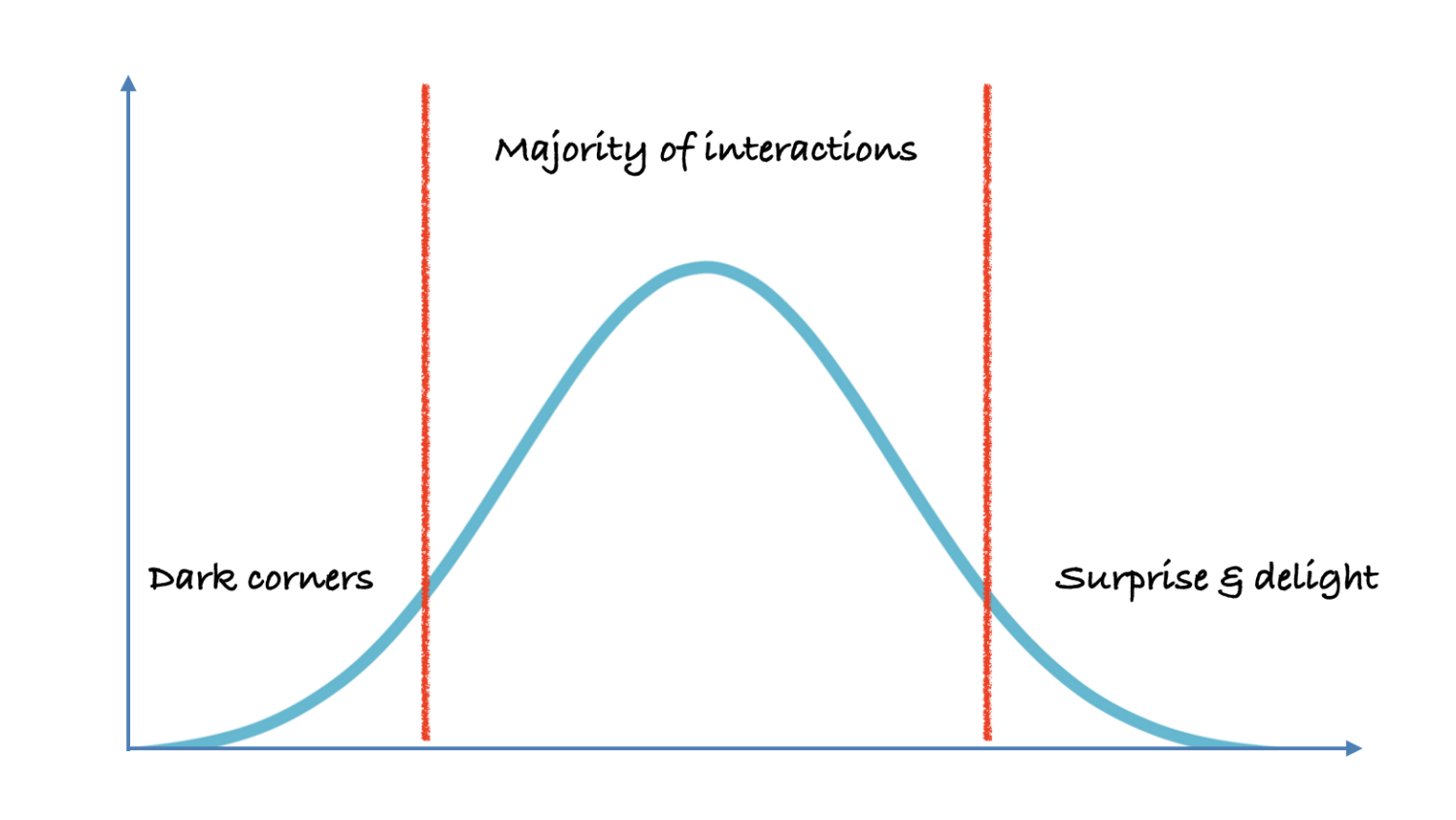

If you think about a normal distribution (bell) curve, then the experiences and services we design tend to cover the 80% of interactions and occurrences that sit in the middle of the bell curve.

The 10% of interactions that sit at the right end of the curve represent interactions that surprise and delight our customers. Now, we might hope that these situations will happen but often we cannot plan for them to happen as they can often depend on the right person doing the right thing at the right time.

Finally, the 10% at the left end of the bell curve is where the really bad experiences sit. But, within that 10%, there are what I describe as ‘Dark Corners.’

These exist in every organization, and when they come to pass, like the stories above, they can have a disproportionate impact on the experiences that we deliver, our organization’s brand and the level of trust that customers have in us.

One way leaders can minimize their potential impact is to first acknowledge that they exist and then go searching for them, shining a light on any that they find and then working hard to do something about them.

Another way is to scenario and stress-test the processes and systems that you use and develop.

No hair-brain scenario should be off-limits

Just ask United Airlines.

This post was originally published on Forbes.com.

Credit: Photo by Linus Sandvide on Unsplash