CX blogs, consultants, programs, workshops, conferences, indexes, frameworks, awards, summits, metrics, NPS – CX is everywhere and widely considered the next competitive battleground. Managers, consultants, scholars, and even politicians seem to agree that the age of the customer has finally arrived and we are better going to be ready for it. The new customer needs new solutions, and blue chips companies like Siemens, IBM, Adobe, Google are standing by, ready to deliver. CRM is proclaimed dead, and CX management in an area where the customer calls the shots is the declared new silver bullet for companies worldwide. Managers read the great CX stories of Apple, Amazon, and Starbucks, and are left wondering how this will apply to their business? Moreover, while we still struggle to coherently define what constitutes CX, we already discuss the next generation of CX management, the role of social media, cloud networks in delivering excellent experiences in the CX revolution you tube channel.

CX established itself as one of the top priorities on companies’ strategic agendas. It really doesn’t matter if we talk about a B2B, B2C, or even C2C context, customers will always have an experience, good or bad, and it will influence their purchasing behavior – significantly. And not only their own behavior, but also the behavior of others; courtesy of the blessing – or the curse, depending on your viewpoint – of the www and social media (Klaus 2013). Our longitudinal global research clearly indicates that delivering superior experiences is, if not the source of, a sustainable competitive advantage. However, while acknowledging CX’s strategic importance is a step in the right direction, the main challenges go beyond acknowledgement.

We explored that companies are struggling with converting CX’s strategic importance into actionable processes leading to increases in performance, and, ultimately profits. CEOs worldwide agree that there aren’t an abundance of options. Either you engage into the big unknown – how to (successfully) manage CXs – or you will loose your customers, and your competitiveness. Moreover, CX cannot be designed, measured, and managed the way businesses managed their product and service offerings in the past. CX management and design is more complex, a well-known fact in boardrooms around the globe. The question on everyone’s mind, though, and the one that managers are struggling with, is how complex is it, and how to manage and design processes to deliver superior CXs?

Marketing researchers, consultants, and scholars propose holistic CX definitions and conceptualizations, in which CX includes all direct and indirect encounters with the company or the brand. I refer to this approach as the theory of everything, in which every single counter seems to be of relevance and importance – a bigger box phenomenon, in which we simply expand existing management and consumer behavior theories in order to explain every possible direct and indirect encounter a consumer has with the company/brand. By including even more possible reasons and triggers, we create an even bigger box, and bigger mystery about what is going on inside this CX black box. If we try to translate the theory of everything into actionable steps, however, it metamorphoses into the theory of nothing. After all, if everything is important, how can a company possibly design a successful CX strategy around this insight?

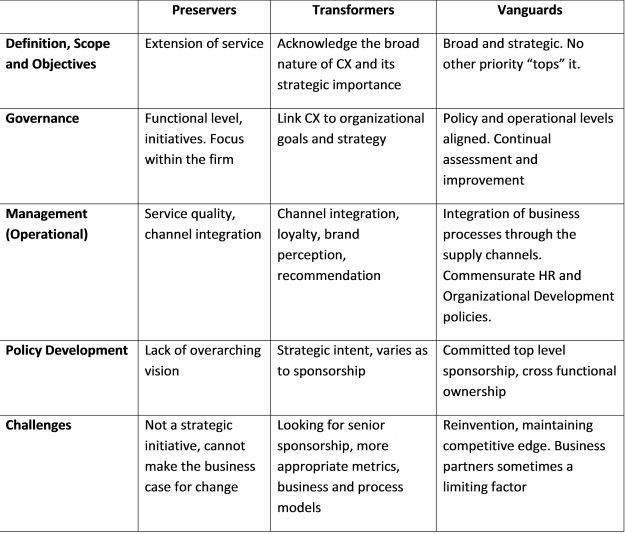

Regrettably, practice doesn’t offer too many truly strategic tools either. The frameworks, models, and concepts put forward range from looking at one particular (design) aspect all the way to high abstract concepts with, forgive me, very little applicable strategic use. The absence of clear guidance on how to design profitable CX strategies triggered multiple of our research projects. We interviewed managers from over 300 companies with an explicit CX strategy and management programs worldwide to gain insight on how the design of successful, i.e. profitable CX strategies can be achieved. We developed a typology of these strategies and CX management practices, identifying three main types of CX strategies and management practices – preservers, transformers, and vanguards (Klaus et al. 2012). Their CX management design differs significantly on all five CX design and management practice dimensions: (1) CX definition, (2) scope and objectives, (3) governance (4) CX policy development and (5) CX challenges.

Preservers define CX management as an extension or development of existing service delivery practices, and assess effectiveness using traditional customer outcome measures of service quality or satisfaction. While acknowledging its importance, Preservers are incapable of making a strong business case for CX to top-management. Preservers’ programs are characterized by a series of limited initiatives rather than a comprehensive program led by a well articulated long term vision, lacking central control, corresponding processes, or an overarching vision.

Transformers believe CX is linked positively to financial performance, but acknowledge its holistic nature and the resulting challenges in scoping and defining its management. This indicates clear internal discourse concerning CX strategy and its management practice. In comparison to a Preserver’s focus on incremental improvements, Transformers strive to become a CX-focused organization, but struggle to develop a CX business model and corresponding business processes.

Vanguards have a clear strategic model of CX management that has impact across all areas of the organization and develop commensurate business processes and practices to ensure its effective implementation. While Transformers merely acknowledge the broad-based challenges of CX management, Vanguards integrate functions and customer touch-points to ensure consistency of the desired customer experiences across their own business and those of their partners. Vanguards recognize the crucial role of accountability and are constantly developing new and better ways to measure the effectiveness and efficiency of CX practice.

In a subsequent stage, we explored the relationship between these CX practices and profitability. The results were eye opening; preservers displayed the lowest profitability score, with vanguards outperforming them by almost 100 per cent. Transformers are, just as their practices indicate, right in the middle between the extremes.

In a subsequent stage, we explored the relationship between these CX practices and profitability. The results were eye opening; preservers displayed the lowest profitability score, with vanguards outperforming them by almost 100 per cent. Transformers are, just as their practices indicate, right in the middle between the extremes.

Managers’ first question, after being exposed to our research findings, is, “how can I become a vanguard.” The answer isn’t as easy as it appears. We do not have yet enough conclusive evidence to determine if all companies have both, the abilities, and capabilities to become vanguards. Vanguards are, by far, the smallest of the clusters – a minority. Vanguards CX strategies are NOT context-specific; they apply across all sectors, industry, company sizes, customer emphasis, and location. Vanguards have both, a clear definition of their CX strategy, and a measure allowing them to track the CX programs impact on profitability. As a matter of fact, often the CX measurement drives the CX definition and the CX strategy design (Klaus et al. 2013). As the old managerial saying goes, you can only manage what you can measure. Consequently, a measurement, such as Customer Experience Quality ‘EXQ’ (Klaus and Maklan 2012; 2013) certainly allows a clear and concise CX strategy design.

I consider myself lucky to live in a period where customers slowly begin to realize that the shift in power towards them is gaining momentum. CX strategy design and CX management are clear signs of these changes. However, as ever so often with change, rather than embracing it, we resist, and only give in if faced with no other option. Our research not only clearly indicates that this time has come, but also that there are great opportunities to be a vanguard in designing profitable CX strategies. The implementation of the frameworks and measurements from our research are reliable and validated tools in assisting managers to guide them on this road to becoming a vanguard, consequently demystifying the CX design black box (Klaus 2014). Their implementation will ultimately lead companies to superior performance and profitability based upon designing and delivering the experiences their customers desire. This is, what I consider a true win-win situation.

References:

- Klaus, Ph. and Maklan, S. (2013), “Towards a better measure of customer experience” International Journal of Market Research, Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 227-46.

- Klaus, Ph., Gorgoglione, M., Pannelio, U., Buonamassa, D. and Nguyen, B. (2013), “Are you providing the ‘right’ experiences? The case of Banca Popolare di Bari” International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 31, No. 7, pp. 506-28.

- Klaus, Ph., Edvardsson, B. and Maklan, S. (2012), “Developing a typology of customer experience management practice – from preservers to vanguards.” 12th International Research Conference in Service Management, La Londe les Maures, France, May/June 2012.

- Klaus, Ph. and Maklan, S. (2012), “EXQ: A Multiple-item Scale for Assessing Service Experience” Journal of Service Management, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 5-33.

- Klaus, Ph. (2014), Measuring Customer Experience – How to Develop and Execute the Most Profitable Customer Experience Strategies, Palgrave-Macmillan.