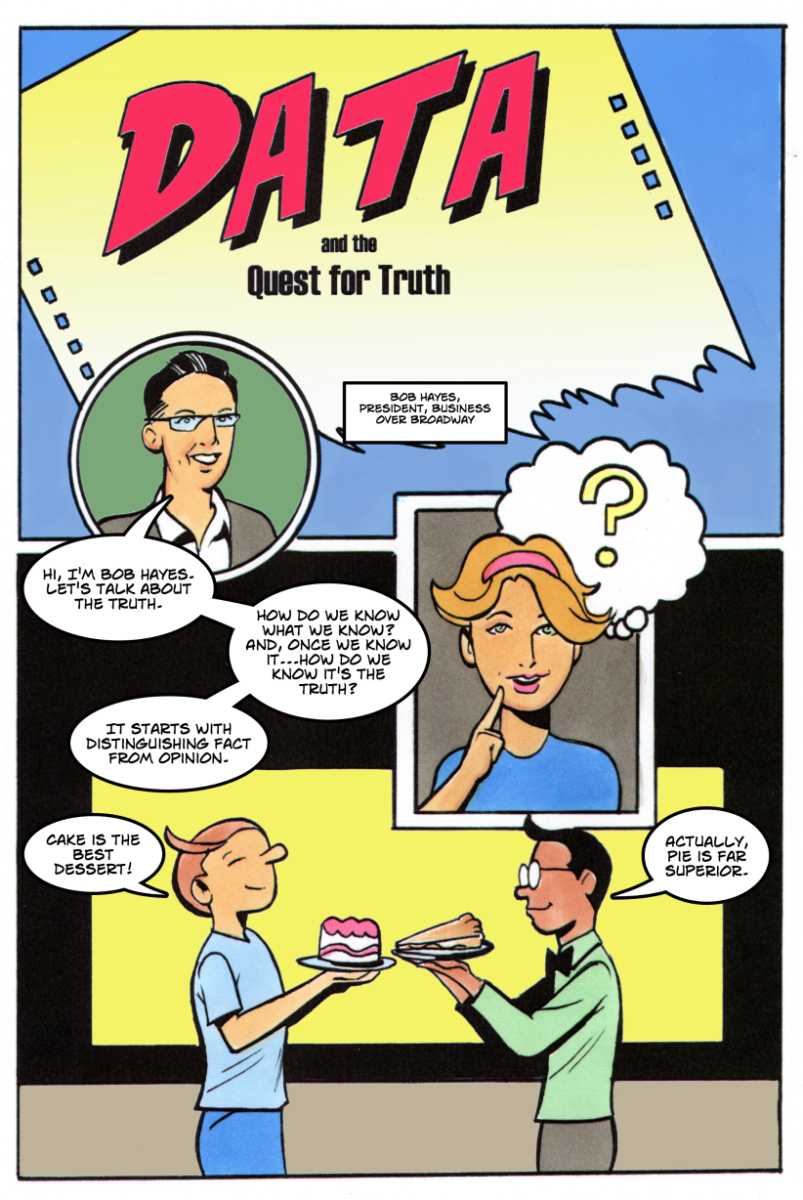

I was interviewed by IBM to share my thoughts on a topic related to data science about which I’m passionate: How do we know what we know and, once we know it, how do we know it’s the truth? IBM turned that interview into a comic strip (see below) and I summarize my points in this post.

You would think that, because we have access to so much information in this digital age, getting to the truth would be relatively quick and easy. As I’ve discussed before, people hold beliefs that are not supported by the information available to them. Take, for example, the 27% of Americans who don’t believe there is solid scientific evidence of climate change, the rise of the “anti-vaxxers” who think that they know more about science and public health than the overwhelming majority of doctors, immunologists and other health professionals, the “flat-earthers” who ignore the ample evidence that the earth is a sphere, the increase in Google Trends that shows that searches of the term “flat earth” have more than tripled over the past two years and more.

You would think that, because we have access to so much information in this digital age, getting to the truth would be relatively quick and easy. As I’ve discussed before, people hold beliefs that are not supported by the information available to them. Take, for example, the 27% of Americans who don’t believe there is solid scientific evidence of climate change, the rise of the “anti-vaxxers” who think that they know more about science and public health than the overwhelming majority of doctors, immunologists and other health professionals, the “flat-earthers” who ignore the ample evidence that the earth is a sphere, the increase in Google Trends that shows that searches of the term “flat earth” have more than tripled over the past two years and more.

I’ve given this topic a lot of thought and I would like to talk about the problems about the importance of everybody gaining some knowledge on statistics and critical thinking (scientific method, evidence-based decisions). Here are few points I made in the interview.

1. Distinguish Opinions from Facts

First, you need to be able to distinguish opinion from fact. While my friend might argue that cake is the best, I might say that pie is far superior. These two opposing views reflect our personal preferences and that’s okay. The problem arises when we argue about verifiable facts. I say the earth is a sphere while he says the earth is flat.

Video Player

2. Watch out for Confirmation Bias

Trying to convince others about the truth is no easy matter. For example, referred to as confirmation bias, people tend to seek out information that supports their preexisting beliefs and ignore information that doesn’t support their beliefs. Also, accepting information is cognitively easier to do than evaluating their merits. So, because we are fallible humans, our beliefs can be driven, not by data, but by a preconceived notion of how we think that the world works.

Trying to convince others about the truth is no easy matter. For example, referred to as confirmation bias, people tend to seek out information that supports their preexisting beliefs and ignore information that doesn’t support their beliefs. Also, accepting information is cognitively easier to do than evaluating their merits. So, because we are fallible humans, our beliefs can be driven, not by data, but by a preconceived notion of how we think that the world works.

3. Statistics and Machine Learning

Statistics and statistical thinking – how we collect, analyze, interpret and organize data to get insights – is the foundation of evidence-based decision making. But we humans don’t have the capability to sift through all of the data that is out there. This is where AI and machine learning come to the fore.

Machine learning allows computers to find hidden insights (i.e., make predictions) without being explicitly programmed where to look. Iterative in nature, machine learning algorithms continually learn from data. The more data they ingest, the better they get at making predictions. Based on math, statistics and probability, machine learning algorithms find connections among variables that help optimize important outcomes. As the amount of data continues to grow, businesses will be leveraging the power of machine learning to quickly sift through data to find hidden patterns. Data scientists, who are simply unable to quickly sift through the sheer volume of data manually, adopt machine learning capabilities to quickly uncover insights to help make better decisions.

While machine learning helps humans explore large data sets that contain a plethora of variables (features), machine learning algorithms are still susceptible to bias. If the data on which those algorithms are based have bias built into them, the resulting algorithms are merely reflecting that bias. A good foundation in statistics, research methods can go a long way in helping data pros mitigate the impact of bias on society.

4. The Need for Data Literacy for All

As a scientist, I believe that the power of analytics and statistics can solve many of today’s problems. This need for data literacy is not only reserved for research academicians but for everybody in the world. We live in a Big Data world in which we are quantifying everything in our personal lives (think FitBit), business (think customer data platforms), healthcare (think electronic health records) and more. The more you understand the basics of statistics and statistical thinking, the better you will be able to maneuver in our quantified world. Think about it. If you live in France and don’t speak French, you’re lost. Similarly, in our quantified (digitized) world, if you don’t speak the language of data and analytics, you’re not going to understand what’s happening or be able to contribute to the conversation. What can people do to improve how they make decisions?

That’s really a problem of knowing what is real vs what is not real. If you possess the true picture of the world, you’re more likely to make better decisions. In general, be inquisitive. When you’re given information, ask questions, not only about the evidence itself, but the source of the evidence. Here are the types of questions you can ask.

- What is the content? Is what you’re being told an opinion or a verifiable fact?

- What is the source of the information? Understand the knowledge of the people and their source. You want to understand how do they know what they know. What sources are cited? Why should I believe them?

- What is their evidence? What this evidence verified? Find out how the study was done and by whom.

- Does the interpretation of the evidence make sense? Don’t simply take somebody’s word as the truth.

- Is the evidence complete? Are you missing something?

President Barack Obama recently talked about the need for humans to accept objective truth, science and the need for critical thinking skills.

Conclusions

While much of the dialogue in the field of data science is around the fear of the rise of artificial intelligence, I’m much more fearful of people not believing in facts and taking action (or inaction) based on bad or no information. To make sense of the world around us and to make better decisions, you must be able to make sense of the data that the world generates. That is, your understanding of the world now requires knowledge of math and statistics. Businesses are savvy to this notion and now rely on data scientists to help them extract insights from the plethora of data they generate and collect. Data scientists combine the power of math/statistics with the power of technology (primarily speed in processing) to extract insights from their vast amounts of data.

Yet we live in a world in which people are operating on their own “facts.” Still others are confusing opinions with things that are known. This sort of thinking troubles me. How are we as a species going to move forward when many people hold beliefs without any evidence? How are we suppose to be a democratic society when a majority of people don’t know how to question/evaluate the power of technology? In our new world of machine learning / artificial intelligence, everybody needs to understand at a basic level how data and analytics works to give us insights.

Enjoy the comic strip!